Civil War Soldiers

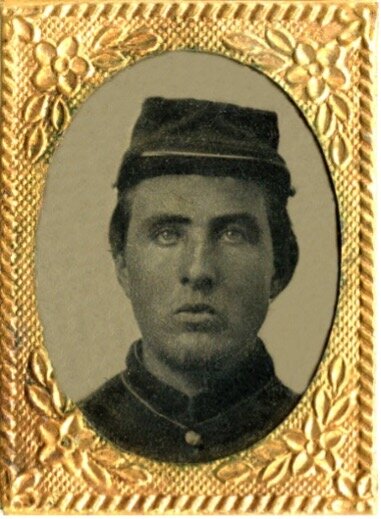

Private Osgood Herrick Dwinnell

by Bill Schuette

Osgood Herrick Dwinnell, was born December 1, 1849, in the township of Spring Prairie, Walworth County, WI.

On the 1860 census, he was listed as being a farmer at the age of 19, living in the Reedsburg area, with his parents, three sisters and two brothers.

In February, 1862, he heeded the call to arms raised by President Lincoln, and enlisted in the Union Army with his brother, Eugene. They were off to save the Union.

During the Civil War, the Sauk County area provided recruits for the Wisconsin 19th, Company A regiment. This regiment served in numerous locations in the East and South, one of them being New Berne, North Carolina. The company was stationed at a place called Evan’s Mill, once owned by a slave-owner, General Evans of the Confederate Army. Company A was stationed there in 1864, to provide picket duty. They were forced to abandon the location when the Confederates attacked New Berne in February of 1864, but several weeks later, when the Rebels abandoned the location, Wisconsin’s 19th, Co. A, regained control of Evan’s Mill.

One of the soldiers of Company A, was Private Osgood H. Dwinnell. He made it through the war unharmed. Just below Richmond he was captured for a short time and released at the end of the conflict.

Recently, a historian in New Bern, North Carolina, was metal detecting in the area that was Evans Mill, and he found a ring with the inscription: Co. A /// O.H.D. /// 19 Wis. This would have to be Osgood H. Dwinnell! This led to additional research into the background of Private Dwinnell. Another historian from New Bern did a search on Ancestry.com and found two documents which indicated that Osgood had been admitted to a hospital in Minnesota, and judged to be “insane”, in 1898, and again, in 1902 for the same diagnosis. Also, the 1902 document indicated that 39 years previous, he had been diagnosed with the same ailment, which would have been in 1863—while he was serving in Wisconsin’s 19th, Company A.

The speculation is that he may have been suffering from shell shock, what we today call PTSD, which seems logical.

"Drew up in line of battle - charged out of the woods into the open field, where we were welcomed by a terrible shower of bullets from the rebel infantry ... some of our best and bravest men fell - still on we went nearly half a mile, until we were left alone in the open field ... ordered to drop down - here we lay, hugging mother earth and praying for darkness and release." -From the diary of Osgood Dwinnell, Oct. 27, 1864

Through a website called Find A Grave, the burial site for Mr. Dwinnell was located in Brandon Municipal Cemetery in Manitoba, Canada. The information provided indicated that Osgood did not have a grave stone. There was only a blank space where he had been interred in 1906. It is the policy of the U.S. Government to provide, at no cost, a marker for any Civil War veteran. A traditional Civil War tombstone was ordered and it arrived at the cemetery last fall. However, the ground had already frozen, so the marker was stored, and installed this spring. Private Osgood Dwinnell can now rest in peace, and those passing by his tombstone can pause and pay respects for a brave soldier who fought to save the Union so long ago.

Postscript - Osgood H. Dwinnell may have been just another forgotten Civil War soldier buried somewhere, someplace, but that was not to be, not if Sauk County Historical Society board member Bill Schuette had anything to say about it.

After Bill discovered located his burial place, Bill learned that Private Osgood H. Dwinnell had no grave stone. So, Bill ordered one through the United States government - which provides free markers for our military soldiers. The U.S. government then sent the stone to Canada last fall. However, the ground was frozen by then and had to wait until spring 2021 for it to be placed on Private Osgood's grave site.

Thanks to Bill and his fellow researchers, Private Osgood H. Dwinnell no longer is forgotten.

Aaron Roberts

Among the hallowed veterans’ graves at Walnut Hill Cemetery in Baraboo is that of Aaron Roberts. Marked with the birth date of October 8, 1848 and adorned with a GAR or Grand Army of the Republic flag holder the tombstone suggests that Roberts was a soldier in the Civil War like many others buried nearby. What is different about the stone however are the markings “CO F 29 CLD INF.” The abbreviations stand for Company F, 29th Regiment of the Colored Infantry indicating that Roberts served in the United States Colored Troops.

Although Baraboo is the final resting place for Aaron Roberts, his story starts in Orange County, Indiana where he was the first-born child of Ishmael and Delaney (Revels) Roberts who were free people of color. His grandfather and great grandfather were also named Ishmael Roberts, the elder having roots in North Carolina where he lived as a free person of color before the Revolutionary War. In fact, great grandfather Roberts fought the British as a member of the North Carolina militia.

In the 1830s partly because life was getting harder for free people of color in the South and land was becoming scarce Ishmael Roberts, Aaron’s father, moved to southern Indiana where he met and married my Delaney Revels and started a family that eventually grew to include eleven children. Sometime between 1854 and 1860, the Roberts family moved to the wilds of Wisconsin as pioneers in Vernon County where some of the Revels family had already settled including Aaron’s grandfather Mycajah Revels who was a larger than life figure. He usually wore clothes he made from skins and furs and always loved his moccasins. He was a legendary bear hunter and once killed three bears one night with his muzzle loader in a big fight.

Aaron was twelve years old when the Civil War broke out. When he was 15 he enlisted by claiming he was 18. The young Roberts was not alone in his service. Five of his uncles also reportedly served during the war with one of them being killed in 1864.

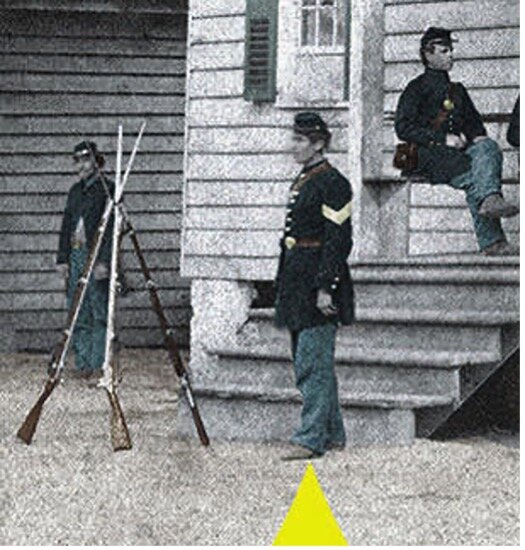

Roberts joined Company F of the 29th Colored Infantry Regiment enlisting in Madison in April of 1864. Company F was credited to Wisconsin, although Wisconsin provided only a handful of recruits, most of the soldiers were really from Illinois or Missouri and agreed to take the place of Wisconsin residents. In all 155 African-American men from Wisconsin served in the Civil War.

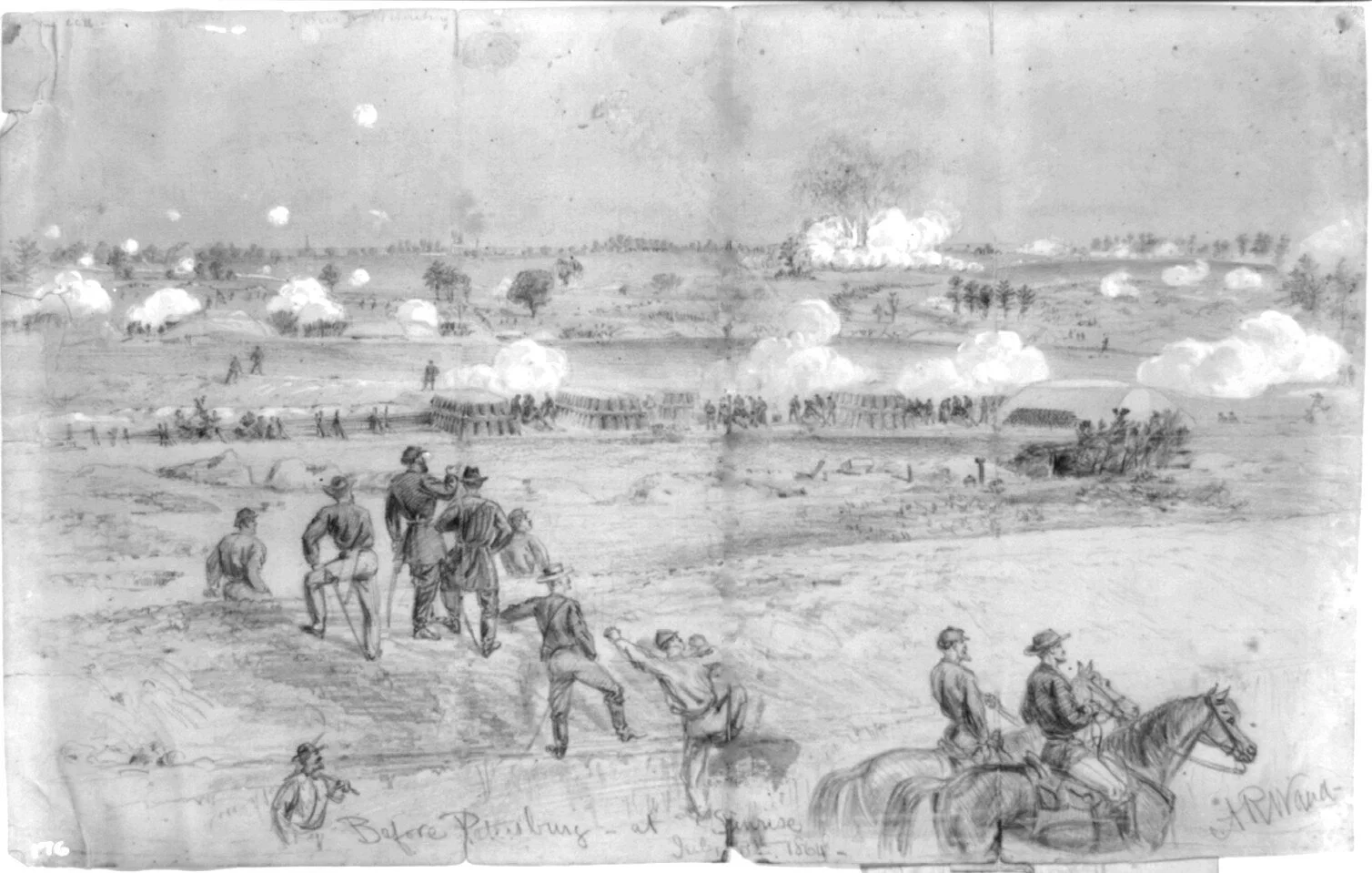

Roberts was present at the Battle of the Crater in July of 1864 which was part of the Siege of Petersburg. After weeks of preparation, on July 30 Union forces exploded a mine blowing a gap in the Confederate defenses and creating a large crater. The attack was unsuccessful though as unprepared Union soldiers failed to break the Confederate line. While the colored troops received severe casualties, Roberts survived unscathed The battle might have been the best chance to end the Siege of Petersburg; instead, the soldiers settled in for another eight months of trench warfare.

Aaron Roberts served continuously until the end of the war when he was mustered out in November of 1865. Returning to Vernon County, he married Martha Stewart in 1866 and started a family. Sadly, Martha Roberts died in 1886. Two years later, Aaron Roberts married Rachel Bostwick. Roberts ran a successful lumber business and later opened a factory producing, staves for barrels and other products. The economic crisis of 1893 caused a downturn in business however and he eventually sold out at a loss.

Roberts spent his later years living in Oshkosh with his wife and extended family and eventually moved to Baraboo where he bought a farm near Walnut Hill Cemetery around 1915. After the death of his second wife he married Della Sebring in 1921 and a few years later the couple retired to a house on Mound Street in Baraboo where Aaron Roberts died in 1923.

The family of Aaron Roberts was part of a notable rural enclave of African Americans in Vernon County, Wisconsin. The area is known as the Cheyenne Valley and is located west of Hillsboro. The 1870 census listed 62 Black settlers among 11 families. Fifty years later the 1920 census listed over 100 African Americans in the area. They lived and worked with other immigrants of Irish, Norwegian and Bohemian descent. Schools and churches were built jointly and there were some inter-racial marriages. Today descendants live far and wide, but some families still have reunions in the area or connect through social media.